Written by Dr. Quinn Henoch

Coaching shoulder position in the overhead squat/snatch lift is a hotly debated topic within weightlifting circles. You may hear things like – “active shoulder”, “reach”, “shoulder blades down and back”, “show me your arm pits”, “shrug up”, “no shrug”, “if you’re upper trap fires – you’ll die, etc. Ok.. maybe that last one is an exaggeration. The point is, we sometimes hear cues that are complete contradictions of each other, but yet, are being utilized for the same exercise.

As a result, athletes are confused as to what an “optimal” snatch grip overhead position looks and feels like, and often misinterpret the words used in the cue. An appropriate coaching cue for any movement is highly dependent on context. So all of ones I listed above could elicit the desired response in a given situation, or likewise, could be misinterpreted.

That is why, in this blog, I will attempt to address some misconceptions and offer simple, practical advice for attaining a comfortable, sustainable, supportive shoulder position for the white buffalo that is the overhead squat.

Discussion Points:

- The Upper Trap – Friend or Foe?

- Internal Rotation – What are we really talking about here?

- Practical Suggestions

The Upper Trap – Friend or Foe?

I’ll preface this by saying that I am not a fan of cueing or even discussing specific muscles in regards to the shoulder joint or scapula. It’s such a complex, 3-D system, in which individual muscles rely on each other for opposition and support. Talking about one particular muscle is likely adding fuel to the fire of confusion. Nonetheless, the upper trap is probably the most discussed (and demonized) of them all, so it’s a pertinent talking point for our purposes. I’ll put it simply – the upper trap HAS to fire in an overhead position. As in, it’s not wrong. It’s just what happens. It’s all part of necessary force couples, in which muscles like the low trap, upper trap, & serratus (and likely contributions from many others) gain leverage off of one another to assist the shoulder blade into protraction, elevation, upward rotation, and posterior tilt. In fact, it’s been shown, that movements in the scapular plane (similar to everyone’s favorite low trap exercise – the Y), that the upper trap is “maximally activated”. Which, personally, I think is absolutely hilarious, considering the common thought process is that we do our ‘Y ‘exercises to train the lower trap, and often cue athletes to avoid any degree of shrug or upper trap recruitment. Basically, what this tells us is that when we lift our arms in the air, our shoulder muscles turn on. Thank science. In seriousness, it reiterates that point that perhaps we should be concerned with positions rather than [demonizing] individual muscles; especially considering those same muscles will be firing just the same in the positions that we desire.

With that said, there do seem to be positions that are more effective/sustainable for supporting load overhead than others.

A common overhead strategy that I tend to steer lifters away from is similar to this:

While these pictures may be contrived, it’s not far from what I see by athletes on a daily basis, as a way to attain a ‘pseudo’ overhead position. The cue of an “active shrug” is misconstrued by translating the humeral head forward and upwards, and pushing the bar back past the plane of the body. During the descent of the squat, the torso drifts forward to accommodate the bar position. As you can see in the third picture, the bar ends up over the mid foot, which is what we teach; however, these compromised levers make it very difficult to support load overhead and rely on passive structures for support. “Hanging on your ligaments”.

Now compare this to the pictures above. In the first picture, I am actively shrugging up and using my upper traps. However, this looks much different than the first picture in the previous series. There is less forward translation of the humeral head, and the bar is stacked over my upper back, hips, and mid foot – and remains so during the squat. This is how we coach, “active shoulder”. It’s certainly an active lengthening, reach, shrug (whatever you want to call it) through the plane of the shoulder blade and humerus, but the humeral head stays flush with the front of the shoulder. “The golf ball stays on the tee”.

Here is another illustration of this in the sidelying position. In the picture on the left, you see the humeral head translated forward and upward; and on the right, you see a humeral head position that is more congruent with the plane of the shoulder blade. This is not to be mistaken as a shoulder blade that’s “down and back”; because we certainly desire elevation and upward rotation of the scapula during an overhead movement.

Internal Rotation – What are we really talking about here?

This is a very similar discussion as the one we had above. We cannot demonize shoulder internal rotation as inherently ‘bad’ without context. What seems to be thought of as an isolated shoulder internal rotation fault during the overhead squat, may again, be a result of global mal-positioning and stacking of the shoulder and bar. Here is what we commonly see:

In this example, the standing overhead position and squatting overhead position are vastly different. The second picture is not simply a matter of internal rotation of the shoulder. It’s a global positioning error as a way for the body to find a passive counterbalance; many times in an effort to attain a deeper squat position. At no point, should a lifter sacrifice shoulder position in order to attain a deeper squat position. Who cares if you can break parallel in your squat, if your shoulders are not in a position to support the load?

I’ve found it much easier to address humeral head and bar position as we did in our Upper Trap discussion, than to cue and crank a lifter into an exaggerated amount of shoulder external rotation.

In fact, there are some coaches who actually cue shoulder internal rotation, which looks nothing like the second picture above. Here’s are examples:

In the pictures above, Mr. Lu Xiaojun (Olympic champion) is demonstrating a relative amount of shoulder internal rotation. However, do you also see that he’s shrugging? Yep. Do you see how he’s actively pushing up on the bar through the shoulder blades, without an unnatural forward translation of the humeral head? Do you see how the bar is stacked and supported over the upper back? This meets all of our criteria for a stable shoulder position, and whether you bias internal or external rotation of the shoulder becomes context and preference specific. It’s not ‘right or wrong’, as long as basic principles guide the experimentation process.

Here’s is a video of a common exercise (screwdriver) that now gives context to this discussion. I prescribe this drill frequently, as a teaching tool for humeral head position, and to gauge the relative rotation (internal or external) that a lifter is most comfortable with:

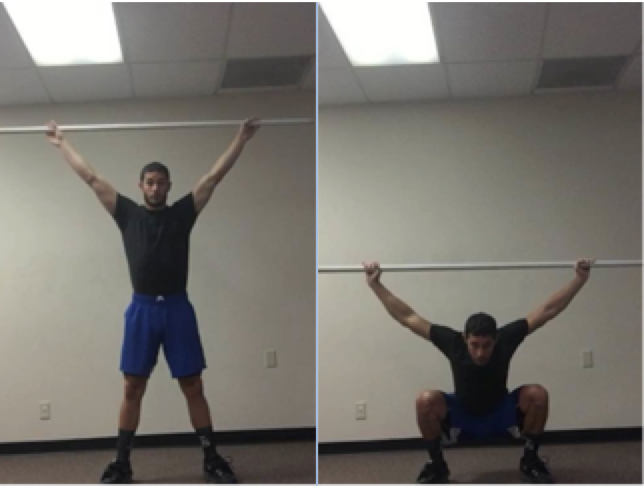

So, what we are looking for when coaching the overhead squat, is for the standing shoulder position (regardless of what rotation bias you choose) and squatting shoulder position to look as identical as possible. Nothing above the belly button changes from beginning, middle, and end of the overhead squat. Think about it like this: if I had a still shot of you from the sternum up, I shouldn’t be able to tell whether you’re squatting or standing. Here’s an example:

Can you tell in which photo I am standing and which I am squatting? It’s probably pretty easy to guess which is which.

How about now?

Did you guess correctly? There should be minimal change between the two.

Practical Suggestions

I am fully aware that there is much more to this discussion than simply telling a lifter, “Do this, not this”; and expecting magic to happen. I concede endless scenarios in which mobility or motor control considerations will make these processes more complicated. However, understanding the basics of the positions is the first step; and trust me, I see just as many athletes who have ZERO mobility restrictions performing the same inefficient overhead squats, as I do those who have “tight” shoulders, hips, or ankles. So, instead of offering up a gazillion possible corrective exercises and stretches in hopes that one of them is your magic bullet, I’m going to offer up some general suggestions:

- Use a Lighter Weight

You probably hate me for this one. And no, I’m not condemning you to a PVC pipe or empty bar for the rest of your life. However, the overhead squat and snatch is a skill that must be learned and honed in environments that are not pushing your high threshold limits – just like any other sport-specific skill. You don’t learn a new free throw shooting stroke in Game 7 of the NBA finals. So, lighten up the weight every now and then, or better yet, take better advantage of your warm up sets at lower percentages. Use those to, dare I say it, get better at the movement and do not be in a rush to make it to your working sets.

- Elevate Your Heels

For some reason, this gets poo-poo’ed by many. There is absolutely nothing wrong with hiking your heels up on plates, EVEN WITH YOUR WEIGHTLIFTING SHOES ON, in an effort to specifically focus on your overhead position during light overhead squat practice. Regardless of if you have a true ankle mobility limitation, elevated heels will provide you with a counterbalance, so that you do not need to worry about falling on your ass at the same time that you’re working on maintaining a stable shoulder position. This is not meant to be a crutch, compensation, or some way of masking mobility restrictions that need to be addressed. It’s simply a way to give the lifter a bit of slack, so that they can focus on a specific goal. Take 5-10 extra minutes each training sessions and practice your overhead position intently.

After drilling the positions with the heels elevated, you’ll find it’s much easier to attain a similar position with only the shoes.

The awesome thing about change plates is that they are different widths, so you can incrementally work yourself back to flat ground.

- Utilize Barbell Variations As Your ‘Corrective Exercise’

Just because you can overhead squat with the depth and overhead position that you desire doesn’t mean it will translate perfectly to your snatch. There are a lot more variables to take into account, when we consider pulling the bar from the floor to overhead and adding elements of speed. Utilizing snatch accessory exercises can be the bridge.

A great example is the snatch balance. It adds an element of speed, which carries over well to the full snatch. However, with the bar on the lifter’s back, he or she can more easily recreate the overhead squat position that’s been so thoughtfully practiced.

Conclusion

There is always “more than one way to skin a cat”, and the cues and positions that work for some lifters may not be effective for others. In terms of overhead position for a weightlifter – experiment with different positions and practice intently. Training is a process and improvement in your positioning is not a singular event. Use the guidelines in this article to augment the corrective strategies that you already use.

This article originally appeared on www.DeanSomerset.com

ClinicalAthlete Weightlifting Coach Certification

We have created a 2-day course that will detail corrective protocols for movement and mobility specifically for each phase of the snatch and clean & jerk. This course is open to all coaches and athletes who wish to improve positioning for the sport of weightlifting and to learn how to effectively integrate that improvement into performance on the platform. For all details and descriptions about the course, visit: www.cwcseminar.com

Our next course is July 23-24 at JuggernautHQ in Orange County, CA. Use the discount code JUGGERNAUT10 to receive 10% off of your registration. This event will sell out quickly, so reserve your spot now.