Written by Team Juggernaut

By Chad Wesley Smith

Over the course of a training plan, as an athlete gets stronger/faster/more explosive (generally more capable of higher outputs), recovery becomes of paramount importance. Over the course of the training cycle, you must begin to remove (or reduce focus on) the less necessary from the training plan. Also you must begin to consolidate the most intensive training stressors to the same sessions/days, to allow for improved recovery on the other days. The idea of consolidating your intensive training stressors is critical because you cannot continue adding to a training plan and you can only intensify so many things at once. The legendary sprints coach, Charlie Francis, likened your Central Nervous System to a cup, all the training you do fills up that cup to a varying degree and once the cup overflows, you have become overtrained. Consolidating intensive training stressors over the course of a training plan is critical to provide recovery time and keep your cup from overflowing.

The first step in being able to consolidate intensive training stressors over the course of a training plan, is to identify what is an intensive stressor and what is not. Intensive training stressors for the athlete consist of the following…

Practice

Practice drills or scrimmages done at competition intensity. This particularly needs to be considered in sports that present a large muscular effort like combat sports, football, rugby, hockey or high sprinting/jumping volumes like soccer, lacrosse, basketball and volleyball. Due to the fact that practice schedules vary so widely and are often without a planned intensity structure, they will not be included within this article.

Sprints

Maximum speed work done at over 90-95% intensity

Jumps

Maximum intensity jumps done in any fashion (onto a box, off a box, for distance, etc). This also includes upper body jumps, ie. Plyometric pushup variations.

[youtube height=”344″ width=”425″]jJECepNeCJ0[/youtube]

At 6-4 and over 300 pounds, Werner Gunthor, displays some of the most incredible jumping ability ever seen (47 seconds into video). Jumps can provide a very powerful training effect to improve strength and speed but most be programmed carefully.

Throws

Maximum intensity explosive throws. These could be medicine ball throws, PUD throws, keg throws, throwing rocks/dumbbells/plates/etc, shot/disc/hammer/javelin throws or even something that is very high velocity/low force like a baseball throw. Obviously for a throwing athlete, some of these drills may fall under ‘Practice’, while other general drills would fall under this category.

[youtube height=”344″ width=”425″]vVsnnRbIX3g[/youtube]

Throwing drills of all varieties are a great builder of explosive power because they allow the athlete to have uninhibited triple extension. While the Olympic Lifts must have a deceleration phase during the final portion of the lift so the bar doesn’t fly out of your hands, throws (whether they be with a medball, pud, shot or keg-demonstrated above by Chad in the 2012 California’s Strongest Man Contest) have no deceleration and allow you to explode throughout the entire of the movement.

SPP Drills

These are special drills that mimic the velocity, duration and direction of sporting activities. These will vary too greatly from sport to sport to list all the options here but an example of an SPP Drill that we use with many of our football linemen and big skill players, called Prowler Explosions, is shown here…

SPP Drills like this can both be done in an alactic and lactic manner depending on the work/rest intervals utilized. Alactic and Lactic capacity work, particularly highly lactic work like that what is often popular among combat athletes, is very stressful to the body and requires ample recovery.

Primary Lifts

These will vary from athlete to athlete but consist of variations of the squat, bench press, deadlift, overhead press/jerk, clean, snatch and rows/pullups. Loading these drills in either a ME manner (over 85%) or a DE manner (45-70% for maximal speed) are both considered hi intensity CNS stressors. Assistance exercises could also turn into high intensity stressors if they are loaded in such a manner, either being done to rep maxes or being performed to failure. Avoid letting your accessory lifts to primary lifts.

Now that we have established what are constitutes a high intensity training stressor, let’s now examine how to consolidate these over the course of a training plan. For the purposes of this article, all of the microcycles we will discuss will be 3 weeks long.

[ismember]

An important idea to understand in the context of this article is output. The speed, distance, weight, velocity capable of being achieved in a given exercise by a particular athlete is its output. Outputs are a measure of absolute speed, weight, distance and velocity, is isn’t relative to the exercise or necessarily the athlete. With that being said, understand that maximum velocity (Yards or Meters per second) is the ultimate measure of sprinting output, weight the ultimate measure of lifting output and distance (either vertical or lateral) the measure of jumping and throwing output. Some exercises are more conducive to higher outputs; for example higher velocities can be achieved in flat land sprints than hill or sled sprints; depth jump variations and multiple response jump variations produce higher ground contact forces and output capabilities than single response box jumps, bilateral barbell lifts allow for greater weight (high output) to be moved than unilateral or dumbbell movements. Also, stronger/older/more experienced athletes are capable of higher outputs and are thus more capable of trashing their muscular and nervous systems by overtraining. For example, an Olympic sprinter is capable of far greater maximal outputs than a high school athlete. For the purpose of this discussion, let’s say that the Olympic athlete is capable of running 28.0 miles per hour while the high school athlete is capable of 23.0 mph. Maximum outputs are much more important than relative outputs in regards to the consolidation of stressors; this is true because the faster/stronger/more explosive athlete isn’t just capable of higher outputs, they are also more efficient in their technique and fiber recruitment and are thus operating nearer their ultimate output potential. To further illustrate this point, think of this, it is capable for many of my high school athletes who run in the 11.0-11.25 range (a good but not outstanding time for a HS athlete) in the 100m to run multiple repetitions of 100m in the 11.1 to 11.37 range, while it is nearly inconceivable for a very highly qualified athlete (9.85-9.99 seconds) to run multiple times within the same range of their maximum speed. As you progress through a program you should move from exercises with reduced output capabilities to those which allow for greater outputs. Below is a list of exercise progressions that allow for continually higher outputs, listed from lowest to highest possible outputs…

Sprints

Uphill Running As, Flatland Running As, Uphill Sprints, Flatland Sprints, Flying Sprints

Lower Body Jumps

Extensive Pogo Jumps, Single Response Box Jumps/Jump for Distance, Multiple Response Box Jumps/Jumps for Distance, Multiple Response Box Jumps/Jumps for Distance, Hurdle Hops, Depth Jumps

Upper Body Jumps

Clap Pushups, Pushups onto a Box, Drop Pushups, Rebound Pushups

Early on in a training plan, for example during the beginning of the offseason-immediately after the competitive season has ended, you need to create breadth in your training stressors, meaning that you must spread your intensive training stressors over many days. Doing this will limit your output capabilities, which is fine during this time period because you will most likely be in a slightly detrained state and wont be capable of high level outputs anyways. During a time when you are dealing with an athlete that has low output capabilities, whether that is because they are coming off a period of a lack of training or have a low training age, you want to create a high frequency training plan to give them as much exposure/practice as possible to various drills. Also due to the relatively low strength levels that athletes like this possess, it is difficult for them to overtrain the CNS. Here is an example of how the first week of such a training cycle would be structured…

You will notice during this phase that sprints/jumps are being performed on opposite days from primary lower body weights. The medium written above each days activities, is referring to the intensity level of the day’s training. This is being done with the intention of limiting output capabilities because obviously sprints/jumps are taxing to the lower body and will limit your output abilities on the next days squats/deadlifts and those squats/deadlifts will limit your output capabilities on the following days sprints/jumps. This is done by design to allow the athlete to allow the athlete to train with a high frequency and learn the necessary techniques of the various movements required to improve speed, power and strength. Also since the athlete wasn’t capable of particularly high outputs during this time period it is fine. The sprint work during this phase should be relegated to power/speed drills such as high knees and skipping drills, hill sprints or sled sprints. Drills like these will further limit their output capabilities, which is necessary at this time to avoid any soft tissue injuries (ie. Hamstring pulls), as the body is not prepared for high velocity sprinting.

In respect to medicine ball throw training volume, you must reduce total throwing volume from week to week because you will inevitably be able to produce higher outputs from week to week due to practice in the movement and continually improving power capacity. Volume must be reduced because intensity is very difficult to limit/manipulate in medicine ball throws.

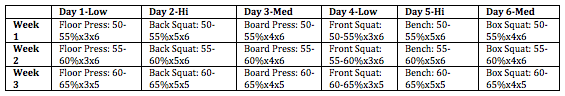

The lifting during this period should be relegated to submaximal loads (55-75% of 1rm) such as that utilized in The Inverted Juggernaut Method or 5/3/1. A great way to organize your lifting during this block is in a High/Medium/Low volume scheme. During this 6 day week you will go through 1 day of high, medium and low volume day for both your upper body and lower body primary weights. You can perform the days in any sequence you choose, but I would suggest doing Low Volume Upper Body, Hi Volume Lower Body, Med Volume Upper Body, Low Volume Lower Body, Hi Volume Upper Body and Medium Volume Upper Body. I would also suggesting choosing 3 different primary exercise variations for both the lower and upper body, this will give you more flexibility when looking to consolidate your work as time goes on which is critical when applying these ideas. For the purposes of this example, we will use the Floor Press, 2 Board Press and Bench Press as our primary upper body training exercises and Box Squat, Front Squat and Back Squat as our lower body exercises. The deadlift and it’s variations are also viable options here, but I choose not to use it with my athletes because it is more taxing to the entire body than the squat is.

3 week training cycle

Utilizing the exercises listed above and a hi/med/low volume structure.

As you move through this period, your output abilities will have increased, as will your need to allow more time for recovery. To help aid in your recovery, we will now consolidate all of your lower body intensive stressors (sprints, lower body jumps, lower body primary weights, lower body assistance training) to the same day. Consolidating your stressors in this manner will also allow for higher outputs because you will no longer be pre-fatigued from the previous day’s training.

Managing weekly training stressors…

During this period you will continue to utilize submaximal weights, as you/your athletes continue to improve technical skills in the primary lifts. Progress you sprinting drills, up one level, ie. Extended Power Speed > Hills/Sleds or Hills/Sleds > Flatland Sprints. Since you are still training with relatively high intensity on a 6 day per week schedule, I suggest that you continue to utilize a Hi/Med/Low volume structure.

3 week lifting wave:

hi/medium/low structure that extends upon the previous cycle…

The 3rd step in a process like this requires a further compression of intensive training stressors. Since you are now capable of significantly higher outputs, you must now change the structure of the training week to reduce the frequency of training. For this we will move to 2 upper body and 2 lower body training days per week, with one day serving as a primary session (Max Effort work) and the second day serving as a supplementary session. The supplementary weights session should feature a lower output exercise as the first movement and should be loaded in a submaximal nature; below I list repetition ranges for the supplementary movements, to ensure that each is being done submaximally you should feel as if 2-3 reps are being left in the tank each set. For sprint training, I would now dedicate one day towards maximal speed work and the second day towards acceleration work.

Here is how I would structure the following 3 week block…

To further consolidate intensive training stressors you must move towards a full body training template, moving all of your intensive training means to the same days, reserving the other days solely for supplementary work and aerobic capacity development drills. The following two example cycles will further consolidate the training means and complete a 15 week training cycle (this cycle could be extended to 18 weeks by taking a deload after the 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th training cycles, which I would suggest)…

The final incarnation of this structure will have you testing 1 rep maxes and will drop the supplementary work from your Day 3 training. Notice that you have now gone from 6 medium intensity days in Cycle 1 during each training week to now finally, 2 extremely high stress days, 1 medium day, 3 low days and a day off. This type of structure will allow for ample recovery between intensive sessions.

Once you have reached this point in your training, depending where you are relative to your competition schedule, you would continue to repeat a similarly structure plan to this final cycle.

Consolidating stressors is critical to perform throughout the creation of annual plan to provide your athletes with increased recovery time as their output abilities improve. You must consider all intensive training stressors when creating a training plan for yourself and your athletes, remember that you cannot continually add training means or intensify too many means simultaneously. Your ‘Cup’ is finite, consolidate stressors to prevent it from overflowing.

[/isMember]

[nonmember]

CLICK HERE to become a Juggernaut Member today and access this complete training cycle. Juggernaut Members get access to all our Members only content!

[/nonmember]